“If we teach today’s students how we taught them yesterday, we rob them of tomorrow”

– John Dewey (1944)

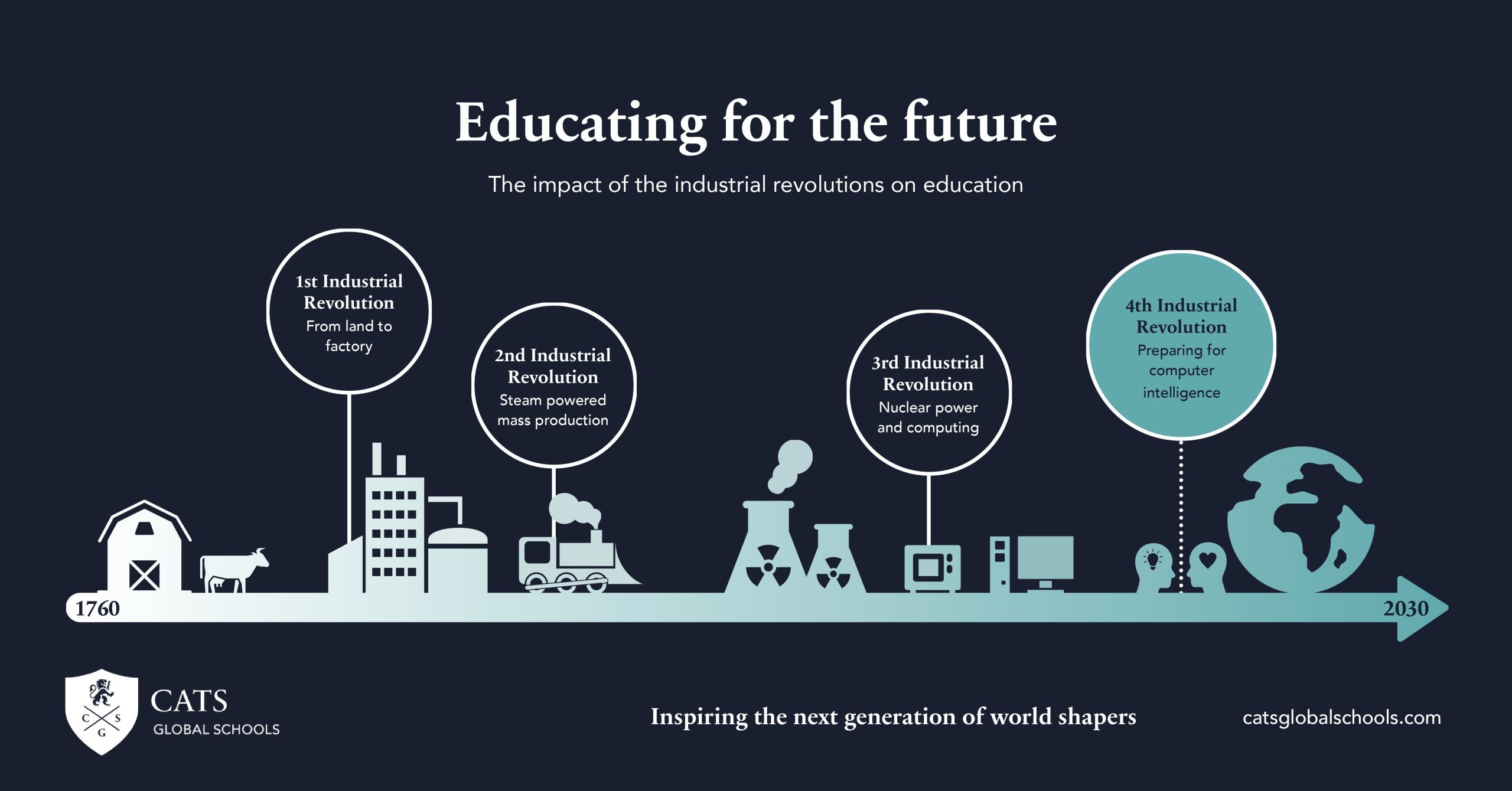

In 2018, the World Economic Forum released a paper entitled “The Future of Jobs” describing how “the Fourth Industrial Revolution is interacting with other socio-economic and demographic factors to create a perfect storm of business change in all industries, resulting in major disruptions to labour markets”.

First Industrial Revolution: Preparing for the land (around 1760 – 1860)

Second Industrial Revolution: Preparing for mass production (around 1860 – 1960)

“The current approach to education reflects its roots in the industrial revolution, the system and the schools within it are designed like a manufacturing process, to take inputs and produce an output but our current outputs are those needed for a bygone era.”

Dominic Tomalin

Principal, CATS Cambridge

Third Industrial Revolution: Preparing for automation (around 1960 – 2011)

“In the last few generations our relationship with information knowledge has completely changed. Education and, to be frank educators, have failed to keep up.”

Dominic Tomalin

Principal, CATS Cambridge

“At some point, the future of education will involve a change to assessing students against the skills they will need in the future and in the ways that they will have to use those skills in life. The pandemic has seen CATS University Foundation Programme (UFP) smoothly move to fully electronic assessment, within a year, so I know that rapid, positive, progress in assessment is possible when there is a will to make it happen.”

Craig Wilson

Executive Principal, CATS Colleges

“The narrow past approach of learning by rote has delayed our progress. Learners today need to be resilient, naturally inquisitive, adaptable and emotionally intelligent. Future learning will focus more on technology and creation of apps. Developing interpersonal skills that no robot can reproduce will become more important than learning pure facts.”

Jason Lewis

Headmaster, Bosworth Independent College